|

Billy Joe Shaver interview |

| Back

to the Books and Other Writing page Back to the Archive Contents page by Elijah Wald Billy Joe Shaver is the father of the Texas songwriter renaissance. Waylon Jennings founded the outlaw movement on Shaver's songs, and they have been recorded by everyone from Elvis to the Allman Brothers, Johnny Cash to John Anderson. His work is beautifully crafted and relentlessly honest, without fancy frills and clever tricks, and many people consider him the greatest writer on the country scene.

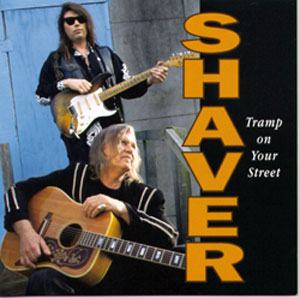

Shaver's singing is the same way, completely natural and convincing, with the dry sound of slow-blowing prairie dust and the ghost of a cowboy yodel at the edges. He has made seven albums without ever breaking out of the Southern honky-tonk circuit, but his new Tramp on Your Street seems to be changing all that. He has joined his son Eddy, a blistering lead guitarist, in a band called Shaver, and the combination of hard-rocking electric power and his pure country vocals is finally getting him some mainstream attention. On Wednesday the band comes to Johnny D's in Somerville, Shaver's first Boston visit since the 1970s. Looking at his songwriting success, including classics like "Honky Tonk Heroes" and "Old Lump of Coal," and the fact that the Rolling Stone record guide routinely gives his albums three- and four-star ratings, it is hard to see why Shaver did not become a hit long ago. The answer seems to be that Nashville has never really figured out what to make of him. At first I was so unique that they let me go on and do my own thing," he says. "But then they started wanting me to change. I had a publisher who told me my songs were too mature, that I needed to write a little more silly 'cause that's what people were wanting. And I thought, well, they can get it from somewheres else. The market is flooded with a lot of young writers -- there's some real good ones, don't get me wrong -- but there's others that're just throwing out crap with barn paint on it, and I ain't gonna get into that.

The new album exemplifies Shaver's strengths. It is heavily autobiographical,from the title ong about seeing Hank Williams in a touring show to "Georgia on

The album has received uniformly rave reviews, and now Shaver is out on the road trying to catch the brass ring that may be finally within his grasp. ''We're driving our old '82 Dodge van that's got over 400,000 miles on it," he says. "And we're just barely making it, but we're going to do more. I'm with people who believe in me and everything's slowly moving up, and hopefully the cream will rise to the top. With the interest generated by such Texan disciples as Joe Ely and Jimmy Dale Gilmore, and country traditionalists like Eddy Shaver's longtime boss, Dwight Yoakam, the time seems right and the Shavers are a unique and wonderful team. Eddy Shaver and the young band of country rockers he has assembled give his father the rock edge that makes for great outlaw crossovers, and the combination of the son's electric drive and the father's dry, lived-in vocals transcends genres and generations. And, at 54, Billy Joe Shaver still has the energy and hunger to play the grueling one-nighters he needs to break through to a new audience. "Even back when I was young, I said age ain't got nothing to do with it unless you want it to," he says. "That's just another barrier we seem to put on ourselves. I mean, I see people out there that are real young -- like in their 20s -- and hell, they're just as ugly as I am." That was all the space the Boston Globe gave me in 1994, but there was lots more. Here are some excerpts: It gets down to it, no matter how soulful you are, you got to realize that you gotta be able to make money to get your music heard anywhere. You know, it's what I work on, I'm real good at it, but it doesn't matter how good you are, you got to have that other part to it. The people I'm with now, Zoo-Praxis, they really believe in me and we've got a real good album, and everything's slowly moving up and hopefully the cream'll come to the top. I don't make much off those songs. I didn't make a very good publishing deal. Michael Jackson owns all my copyrights. He went over to London and bought that ATV catalogue. Well, he didn't buy the whole catalogue, he just bought all the Beatles stuff, and I don't know how they accidentally got mine too. I wouldn't think he'd be caring that much about something like me, but anyway he got mine too. And he's got different people administering the catalogue, like SBK started out administering 'em, and then it went to CBS songs, and now it's at MCA or EMI, and every time it'd change, my checks seem like they'd get about half as much. And I swear I don't believe I've ever been paid for domestic royalties. Just foreign. I know some of my friends went ahead and had 'em audited and stuff and come out with a whole bunch of money, but I never have done that. I guess I might have to do that. I got divorced also, in '86, so half of it goes to my ex-wife. I came up to Nashville in 1966 and laid around, played around there for a while. At that time, about all I could do was write. I could do the other too, you have to be able to do a certain amount of it, but I ran into some guys who could sing a whole lot better'n me. Was Waylon Jennings, Bobby Bare, and guys like that. And I wound up being more of a writer and people didn't pay too much attention to my singing. I always knew I could make it as a singer, but I made it as a writer before that. But I can't imagine anybody singing any better'n Waylon. It's hard to keep from being cute or using a lot of tricky lines, those hook lines and things like that. I've got a lot of lines in my songs that usually after I put 'em out somebody winds up writing a whole song about that one line, and it's just a throwaway line. But that don't bother me, because I write the same way the whole time and it's not gonna change. It comes to me in all kind of different directions. Sometimes it comes to me just like poetry, and then sometimes it'll come all at once, music and words. And sometimes it'll seem like one'll just fly through there and just write itself, like five minutes or so. I've got a theory about that—course I don't know, it's difficult to explain. I'd like to think I was clever enough to know every move I'm making at the time, but I don't think I am. It's already inside of me, and sometimes it just rolls out in one thing, and no telling how long it's been rolling around inside of me. I have some that I've carried around for years, just carried around because I loved it so much working on this one. Most of the times it'll be one that's not commercial at all. It's almost like a fellow that's working in a wood shop or something, making real good furniture or something like that. Some of it you realize if you go too fast on it, it's not gonna be as good. That's why I've held back going with these big publishing companies. These large companies—I ain't gonna name no names, but you know who I'm talking about—they make you sign a thing that you're gonna write with whoever they tell you to write with. And you're liable to end up writing with three or four guys on one song. And to me, soulfully, that just don't make sense. You know, I've had a few songs that I've written with other people, but I always ended up writing 'em myself and giving them half, so there wasn't much need in me doing that anyway. I was born again, yes, but it's not like these other people are talking about. I just got a new start. When I went up on this mountain outside of Nashville, way back there, I can't remember how far back. You know, I was into all of that outlaw stuff. I was running and raising hell with everybody and I was doing probably twice as much as everybody else. And it got to me. I was fixing to die, I knew I was. And I had a vision—we won't have to go into that, but I wound up one night way out at a place called the Bends of the Narrows on the Harpeth River. And there's a big old mountain out there and it's got a big cliff on it. My son had taken me out there with a bunch of his friends, and there's an altar up there on top, looks like where the wind or rain or something had sometime or another hewn it out just like it was a real altar. And it struck me as a real spiritual place. And I wound up in the middle of the night going out there. Back then, that was before they discovered the place, it didn't have any trails to speak of and stuff like that. I just climbed up the mountain on this one little bitty path, pretty treacherous really, and I got up there and I was either gonna jump off the cliff—actually, I thought about just jumping off the cliff to tell you the truth. I know it sounds awful crazy, and I guess I was back then. But I wound up on my knees, down at that altar, and I asked the lord to help me write a song. (laughs) 'Cause I couldn't seem to even put a sentence together, I was so far gone. And I came down that mountain after lots of things took place up there, I came down that mountain, and I was singing that song, "I'm Just an Old Chunk of Coal, But I'm Gonna Be a Diamond Some Day." I had the whole first part of it finished before I got all the way down the mountain. And then I went on back to the house, and everything changed for me. I just went cold turkey, no cigarettes, no booze, no dope, no nothing. And about two weeks later I packed the whole family up, and just moved off to Houston, just right back middle of the time when I could've really been popular. But it just was in my heart to get out of there, because we were all doing lots of things we didn't need to be doing. Mostly me. But I still had hold of the family and chose where they went, and we loaded up and left. Course, things went down for me. I was still with ATV publishing, and they dropped me, and then I had some record deal and they dropped me, and all those kind of things happened. I got to Houston and put in a year there, and Willie called me up on the phone, he said "Won't you come on out and go with me and Emmylou, we'll put you on in front of us and you can make a little money and get yourself on your feet again." And so I did, God bless Willie, and went on and got up again. And things gradually have come up and , as a matter of fact, as this album came out, they sent Willie a copy and he called me from New York to say he just loved the album, he thought it was really going to do it for me, and he put me on a bunch of shows with him. Again. Willie comes along just when I need him, he's the greatest guy in the world, I swear. When [Eddy] started playing guitar was the day that I got so frustrated—I always had trouble tuning a guitar, and I got so frustrated with this guitar I said, "God, please help me with this tuning." They didn't have tuners back then, or I didn't know about them. Sometimes I'd call my friends up and say, "Is this it?" ding, ding, ding, pow! break a string. It just about drove me crazy, and I finally one day just throwed the guitar down on the couch. I says, "I ain't gonna mess with that damn thing any more, I'm just gonna write it and worry about the other part of it some other time." Eddy, he was sitting over there, and I went in the kitchen for something, and I come back in, I heard something playing, and he’s just playing the fire out of that guitar. I said "Eddy! When'd you start doing that." He said, "Oh, I picked it up, I been doing a little bit." I said "Wooee me!" I said, "Can you tune it?"He said ," Well, sure I can." So that's how that worked. He must've been around twelve or something. [About “If I Give My Soul,” in which he asks if his lady will take him back if he gets religion.] Most people that are outside the spirit and are on the verge of getting in, or in trouble or something of that sort, and don't know Jesus, that's the questions they ask. Even though it repulses some people, they say "Why would you want to ask for things for your body and things for this and that?" Well, why not? Why wouldn't they want to ask for this and that. That's the most honest thing they actually can do. I've heard guys say, “Well, if he can help me get out of this mess I'm in, yeah, I'll do it.” It's real honest. We're driving our old '82 Dodge van that's got over 400,000 miles on it. It's still coming along. Course, I've turned into a real mechanic now. We're just barely making it, but we're gonna do more. By Elijah Wald © 2020 |

Asked what makes his songs different from the ordinary Nashville product, Shaver is typically straightforward. "I know my limitations and I write within a realm that's simple," he says. "It's real hard to write simple and stay simple but, when you get it down, simplicity don't need to be greased. Anybody can understand it, if you keep it within that range and write as much as you can with as few words as you can."

Asked what makes his songs different from the ordinary Nashville product, Shaver is typically straightforward. "I know my limitations and I write within a realm that's simple," he says. "It's real hard to write simple and stay simple but, when you get it down, simplicity don't need to be greased. Anybody can understand it, if you keep it within that range and write as much as you can with as few words as you can." a Fast Train," with its lines about "a good Christian raisin' and an eighth grade education," and some late-night love songs. Several songs take a frank look at his turn to religion after years of "doing all of that outlaw stuff, and probably twice as much as everybody else." Shaver avoids the syrupy sentimentality of much country gospel, approaching God with his usual directness and wry honesty, and these songs fit seamlessly with his secular work.

a Fast Train," with its lines about "a good Christian raisin' and an eighth grade education," and some late-night love songs. Several songs take a frank look at his turn to religion after years of "doing all of that outlaw stuff, and probably twice as much as everybody else." Shaver avoids the syrupy sentimentality of much country gospel, approaching God with his usual directness and wry honesty, and these songs fit seamlessly with his secular work.